It’s hard to believe how quickly this summer went by. Over the course of Digital Scholarship Summer Fellowship 2021, we as a cohort and community have explored the digital humanities through group discussion and lived experience. A summer’s worth of work has reinforced that digital humanities is truly what we make of it.

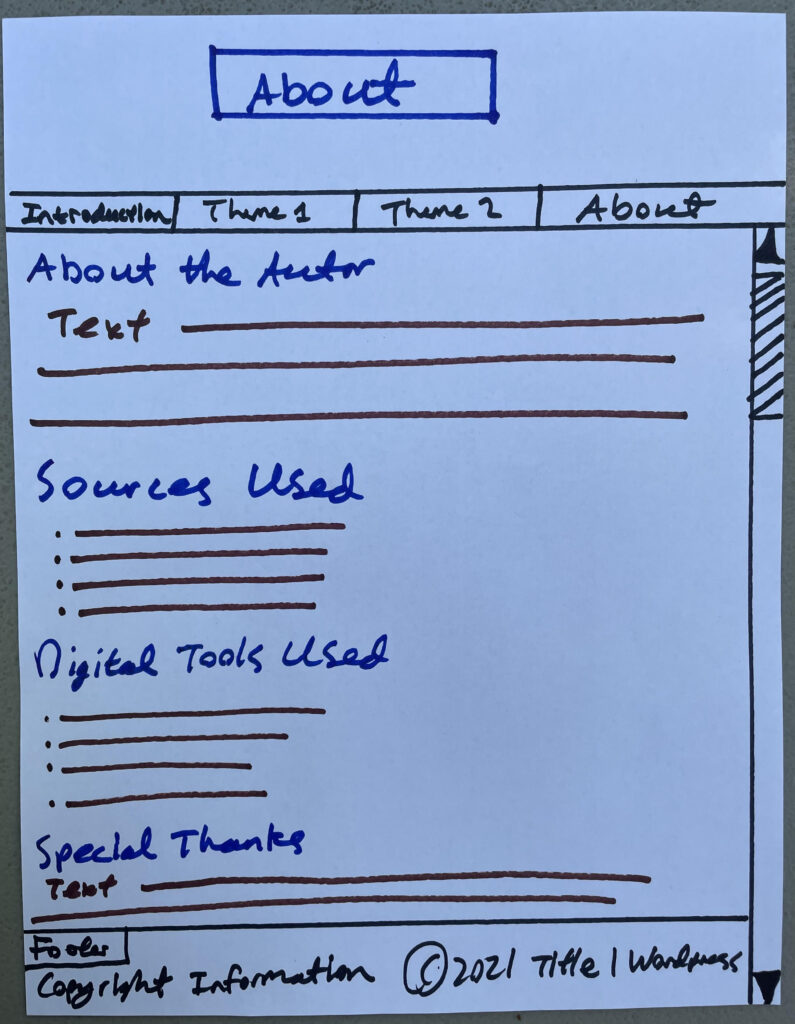

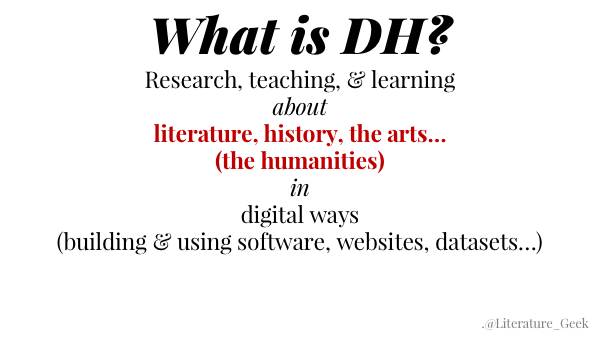

In my first reflection post, I explored Amanda Visconti’s definition of DH in A Digital Humanities What, Why, & How (DLF eResearch Network Talk): “Research, teaching, & learning about literature, history, the arts… (the humanities) in digital ways (building & using software, websites, datasets…).” This definition still feels like the perfect “elevator pitch” overview for those who are confused on the terminology associated with DH. The variety of ideas and digital tools found within each of our cohort’s individual research projects demonstrates just how different DH can be or mean to those in this community.

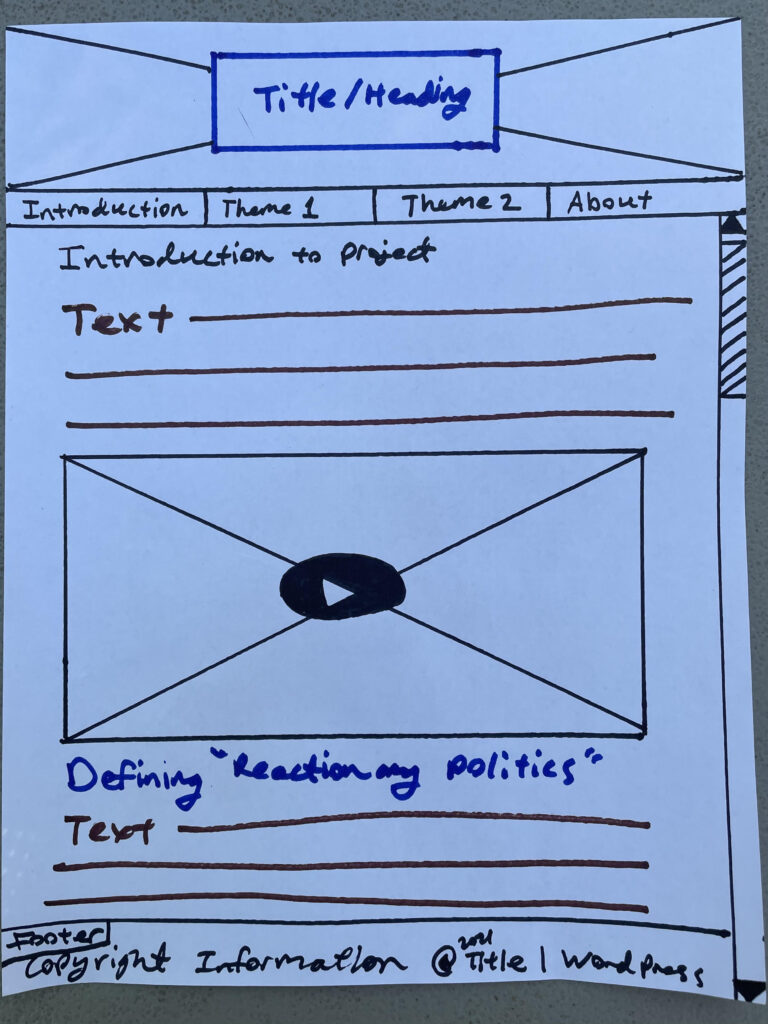

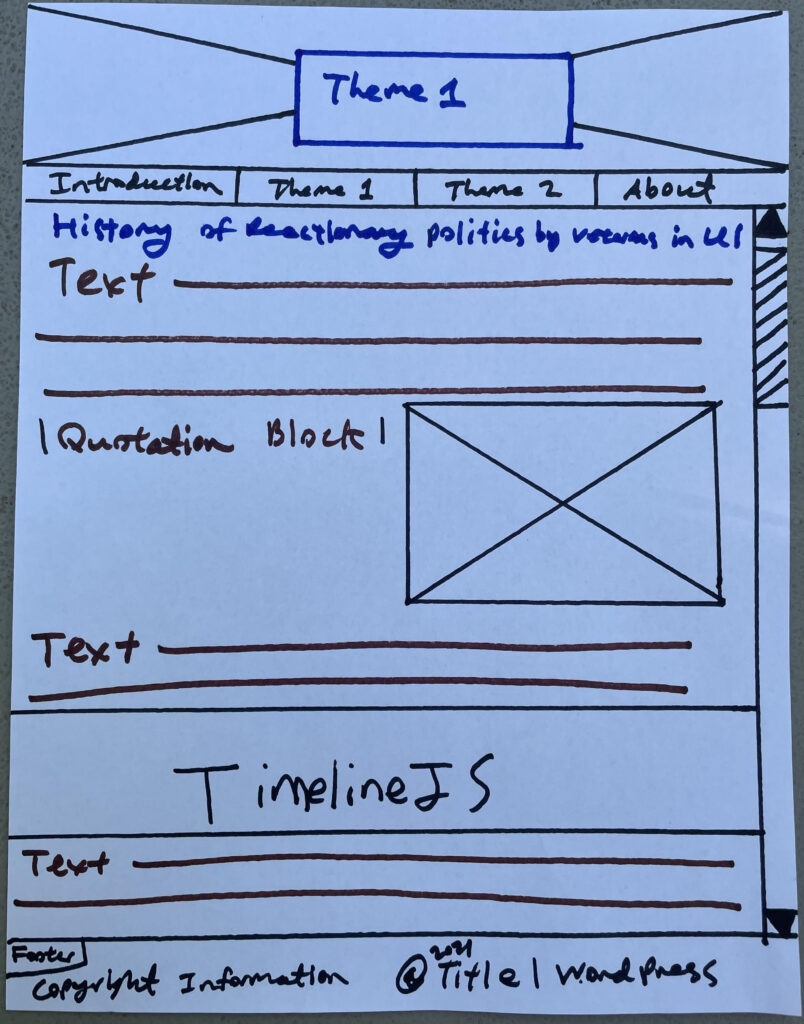

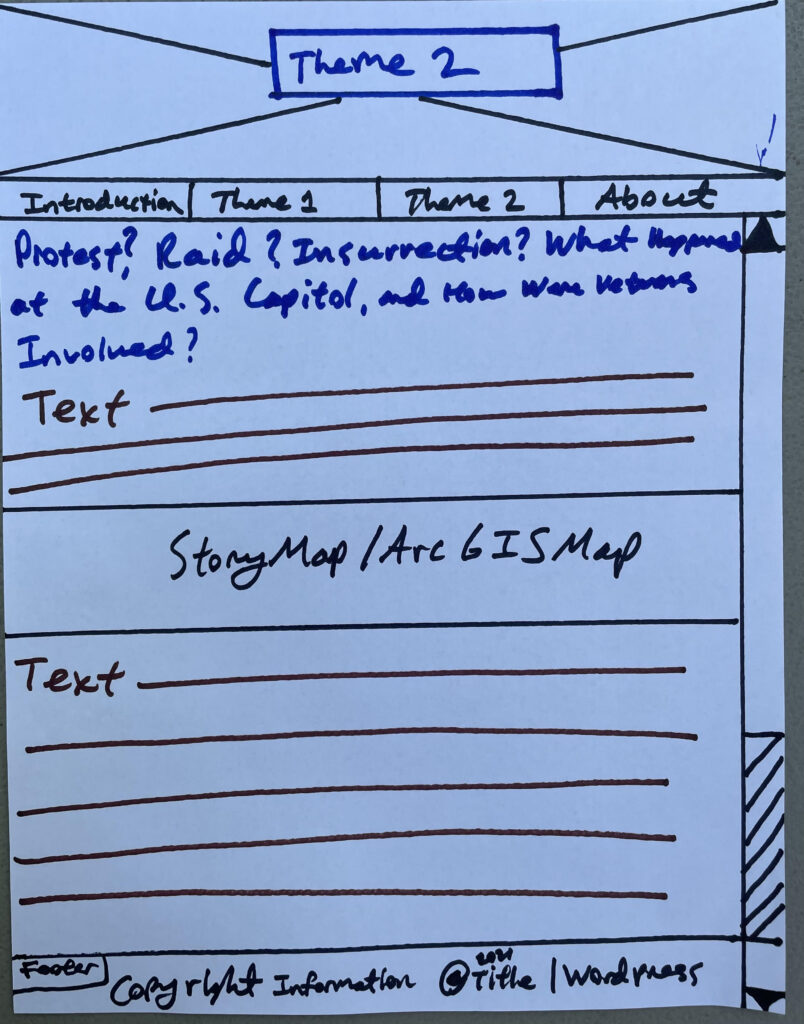

As I mentioned previously in my first post, there are five main values of digital humanities which Lisa Spiro spoke about in her book chapter “This is Why We Fight: Defining the Values of the Digital Humanities.” These five values are: Openness, Collaboration, Collegiality/Connectedness, Diversity, and Experimentation. All these values were meaningful to me throughout my work this summer. However, the value of experimentation most closely guided me when I approached my individual research project. I encouraged myself to integrate different tools, look at sources from multiple angles, and analyze how my website would be navigated and understood.

I went into this summer ready to dive into my research project. I was sure of my abilities to learn the tools of the trade. I initially understood digital humanities as another academic discipline; one that had a recognized definition and correct practices associated with it. I can’t adequately describe how thankful I am to have that preconceived notion shattered. I have come to know DH as an ever-evolving opportunity for thoughtful work available to everyone with the means and ways to contribute to it. That said, access to the internet and technology will always be a challenge connected to the inclusivity of DH.

As a DSSF cohort, we have had the opportunity to explore what DH means to each of us, through engaging in it every day. My exploration has taught me to experiment, and to challenge how I create effective research. My understanding of DH has changed over the course of the fellowship as my interactions with it have changed. Furthermore, how I approached constructing a data visualization differed after discussing the importance of user experience. I learned not only how to present my research so that it would be most effective, but also why I should do so. Eight weeks of exposure leaves me feeling that I’ve only touched the surface of what DH has to offer. I end my experience with DSSF 2021 feeling more curious about what the digital humanities are and mean than I did starting out. While I certainly feel more knowledgeable about what DH can do for individual researchers, and how to create and present the research I have done in the realm of DH, I understand that my experience is only one small part of the greater mosaic that is DH. But after all, isn’t that the point?

This post was written by Ben Johnson, Gettysburg College Class of 2022, and member of the Digital Scholarship Summer Fellowship Cohort 2021.